Close to Me

The magic properties of the perfectly sequenced mixtape

Our family trips were taken in an oversized 4 door blue Chevy Malibu. It was probably the most basic car you could buy in 1977 that would cart around 4 people along with all the stuff they’d need for vacation. My cousins used to joke that it looked like a cop car. I think it was the hub caps that did it.

Really, basic is a generous description. This car had no air conditioning, rear windows that didn’t roll down (at all; by design), and (crucially) a cassette-free AM/FM dial radio that fed mono static to one speaker in the front dashboard and one in the rear deck.

It’s not that cassettes didn’t exist in the 70s—they were a huge upgrade to 8-tracks and were quite common. We just didn’t have a lifestyle that could accommodate common luxuries.

As anyone who grew up before the ubiquity of rear-seat mounted displays or personal electronics will tell you: the scenes from National Lampoon’s Vacation that feature family sing-alongs and back seat squabbles are touchingly accurate.

Of course nothing in real life is ever as touching as a 30 second vignette leads you to believe. As a matter of fact, touching was one of the things that was off limits.

Our big family trips were to either Eastport, Maine, eastern Pennsylvania, or Pittsburgh. The shortest of these from home-base (northeast Connecticut) was roughly 6 hours. When you’re 10, six hours feels like 20. When you’re baking in the backseat of a car in July with no A/C and windows that don’t open, it’s an eternity.

At least the seats were cloth.

My sister and I had games, toys—plenty of ways to entertain ourselves. Mom made sure of that. Plus books—lots of books.

But sing-alongs. You mentioned sing-alongs. What did we sing along to? Certainly not whatever was on that terrible radio—I don’t think it even had an antenna.

Not that we didn’t try.

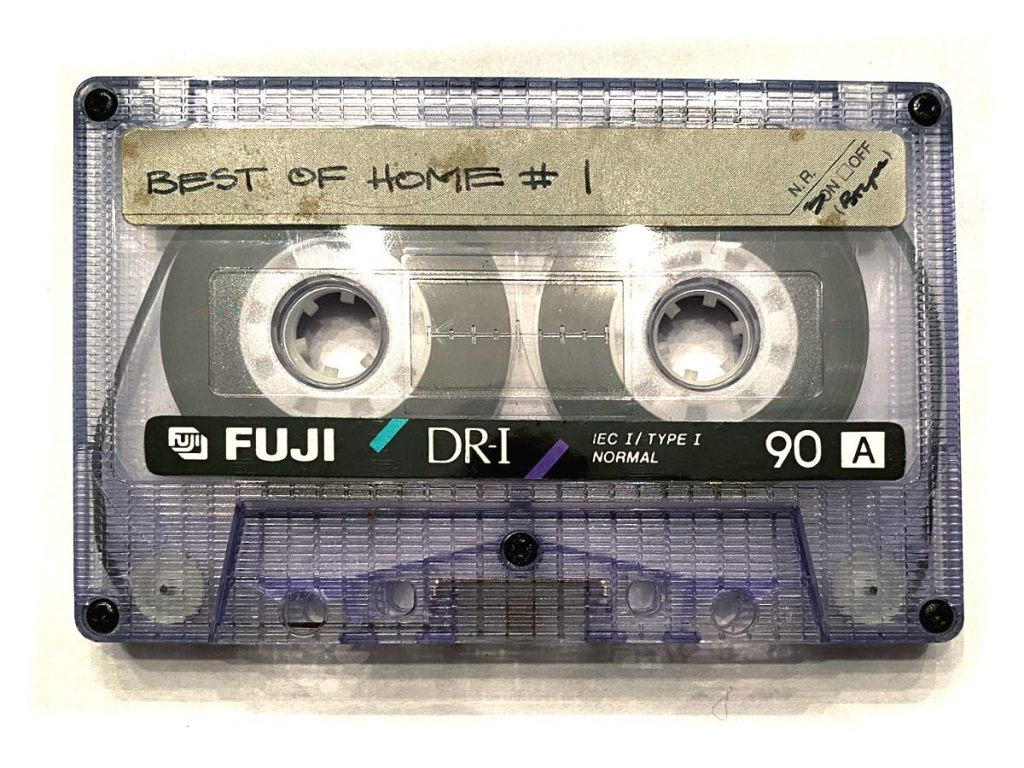

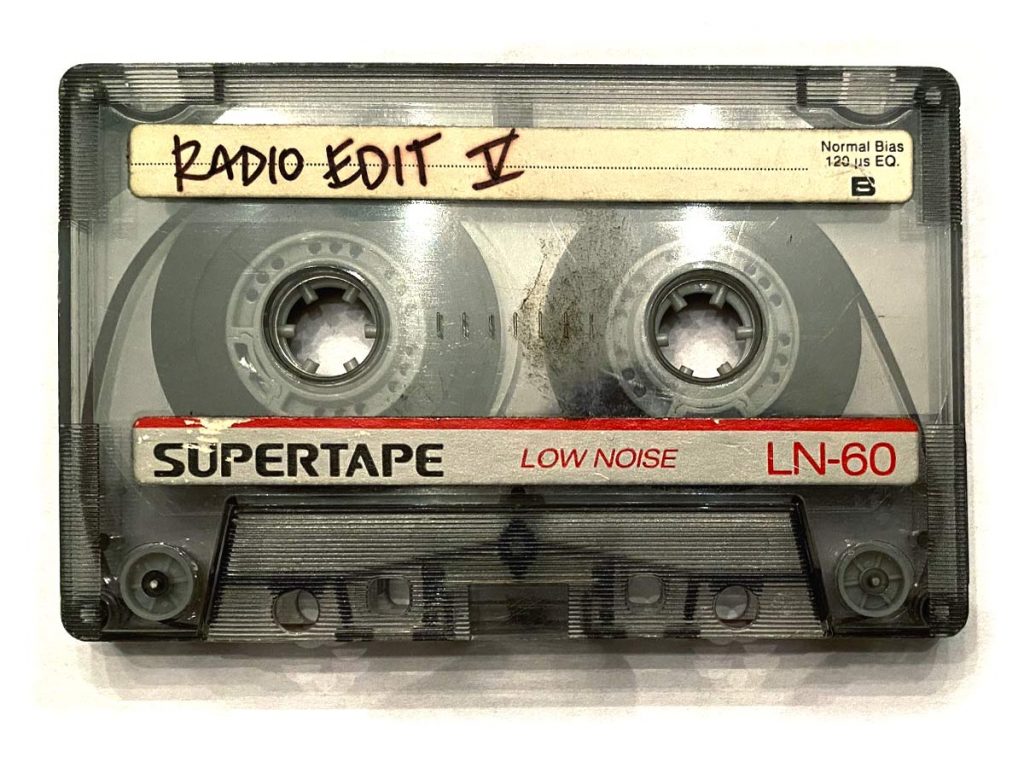

What our happy clan did have for these lengthy trips was an old school cassette player.

If you know what I’m talking about you’re either of a certain age or you’ve glimpsed one in a period movie or TV show when someone in a jail is having a conversation with someone who wants to record the conversation.

Most cassette recorders of the 70s were similar: they were all flat and rectangular—about the size of a 300 page hard cover book laid face up on a table.

Along the bottom of the recorder were a number of levered buttons that each locked into position when you pressed it down all the way. From left to right was Eject, Record, Play, Stop, Rewind, Fast Forward, and pause. The Play button was usually twice the width of the other buttons. If you wanted to record something, you’d push the play and record buttons at the same time. Later models sometimes had the record button inset into the play button.

If you wanted to load or eject a cassette, you’d press the eject button and a plastic cover just above the buttons would pop open and you’d load, flip, or unload your music.

Just above the cassette dock was a speaker. The grille was usually metal that was perforated in the shape of the speaker, typically a circle. The speaker wasn’t designed for good sound.

Between the buttons and the cassette dock was a counter with a counter reset button. Everything on this device was analog and so the counter was constructed of three wheels that each counted up from zero to 9 in consecutive order starting with the rightmost wheel.

Most cassette decks has a similar indexing system that this counter helped establish and track. The theory was that you could reset the counter with each new recording and write down an index for whatever it was you were recording—000: Benny and the Jets, 053: Tiny Dancer, 096: Rocket Man, etc. That way (in theory) you could find a song on tape more easily later.

Most people ended up putting in a tape and listening to it all the way through, flipping it and listening to the other side. Easier to do the editing when you were making the tape than to try and edit a mix on the fly.

This is what my parents did. They had to have spent weeks making mix tapes for our trips. I don’t actually remember them making tapes, but I’m pretty sure they didn’t fall from the heavens in just the right order. Somewhere around 5 mix tapes—30-45 minutes per side—made their way up and down the east coast with us every summer.

Since there were only 5 of them, we knew them all intimately. Every song, every break, every needle drop, every crackle was burned into our memory of these trips. To this day, I can’t hear the closing strums of Lay Lady Lay without expecting to hear the opening fiddle of Devil Went Down to Georgia right after it.

A good mix tape has that effect. It reprograms the meaning of certain songs, forces you to consider a lyric in a different way, and completely recontextualizes a hidden gem into a brightly polished diamond.

There probably wasn’t anything like the mixtape before cassette tapes became ubiquitous. For the first time in the history of music, the non-musical fan could participate. If you didn’t like the sequencing of songs on your favorite album you could change that. Want to remove a terrible song from a track listing? Easy—make your own mix!

Singles were always a thing, but one of their main purposes was to get you to buy the album. Sure, everyone from the 80s has a pile of 45’s of singles with unique b sides or because you just loved that song a ton and didn’t want to buy the whole record.

Artists at the time were mostly writing albums—works of art glued together as a cohesive whole—that had a few hooky singles primed for radio play.

Sometimes that glue was a narrative—a concept album with recurring characters and themes—but usually it was stylistic. Artists would hire a producer, go into a studio for a month or a year and bang out an album of material that captured the zeitgeist of the band where it was at that very moment. It was part time capsule, part expression.

The cassette tape gave those of us who previously only had two options for music consumption—radio or vinyl—the tools to deconstruct either and build our own artifacts to the same purpose. With our own glue.

My earliest mix tapes were made on a personal radio/tape player made by Emerson. It was silver colored, had a dial on the side for tuning am or fm stations, a single mono speaker on the front, and a tape player/recorder that I used for making and playing back my tapes. It had a convenient handle for carrying around. It was about half the size of a box of cereal.

The only source of music for my earliest tapes was radio. The ramifications of this fact were significant.

I had started listening to pop radio a few years earlier. I had a few records but without an income source, radio was the only real avenue for discovery or hearing your favorite songs. A great gift for me at the time was a 3 pack of 60 minute cassettes which I would dig into ravenously the second I could get them out of their plastic bag.

Here’s how I made tapes off the radio in the early 1980s with an Emerson model 1661 radio cassette player.

- Tune into my favorite radio station.

- Insert a blank tape.

- Press play and wait until the scratchy noise from the tape leader goes away and hit pause.

- Reset the counter to zero.

- Grab a pad of paper. Write down 000 and leave the first line blank.

- Press the record and play buttons while the pause is still engaged.

- Wait.

- When a song is almost over, press down the pause button.

- As the next song begins, release the pause button.

- Is this a song I already have or don’t want? Hit stop. Rewind and reset at 000. Otherwise celebrate the new song!

- Write down the name of the song next to 000 on my pad.

- As the song nears its end, prepare to hit pause as I watch the counter.

- The next song will start. Write down the counter index number. (e.g. 032)

- Is this a song I want? Don’t touch any buttons and write down the song’s name next to the counter index I wrote down in 13. Go to step 12.

- Not a song I want? Hit stop and rewind to the number I wrote down as the next index. Go to step 6.

- If at any point I’m nearing the end of the available tape, cross my fingers that I’ll get the rest of the song. If it’s close, flip the tape and go to step 3.

- When the tape is finished, listen to it. Repeatedly. I’ll snap off the tab on top for both sides of the tape so I won’t introduce gaps by unintentionally hitting the record button when I press play for my favorite song.

- Transfer the names and indices to the tape jacket. Name the tape. Be original. Make designs for the cover and flourishes for the title.

This process was rarely carried out in a single sitting: hours could be spent filling just one side of a 60 minute cassette with new music—an entire tape could take a week or more.

But when you were finished…

What started out as an attempt to hack the radio system so an 11 year old could hear his favorite music whenever he wanted became a primer for how music works. Not in a technical sense, mind you—the creation of music was something I wouldn’t fully appreciate until later—but an emotional one: how music connects us.

I had favorite songs. My sister liked many of the same songs. My babysitter did too. (I owed a lot of my early pop leanings to my babysitter at the time). But further afield my taste didn’t always stick. A song that I thought was amazing would be rejected out of hand by a friend who would in turn introduce me to one of his favorites—which I didn’t really much like either.

I realized that I had edited down something general (what was on the radio) to something specific (a mixtape) that reflected me as an individual. These were MY songs. While individually I might share each single with a million other people. But as a collection, this was unique—like me.

I’m not going to give 11 year old me credit that this was a conscious realization, but I do believe that it was the kindling that fed a fire that kept me making tapes through college.

While I didn’t have an opportunity to choose the sequencing of songs (the order was randomized by radio play), it was obvious when it worked and when it didn’t. This was a key lesson in making mix tapes.

Listening back on these tapes (yes, I still have a few) it’s an interesting window into my life back then. Not only are they convenient time capsules for the music that we listened to at the time, but they’re triggers for memories of long lost moments.

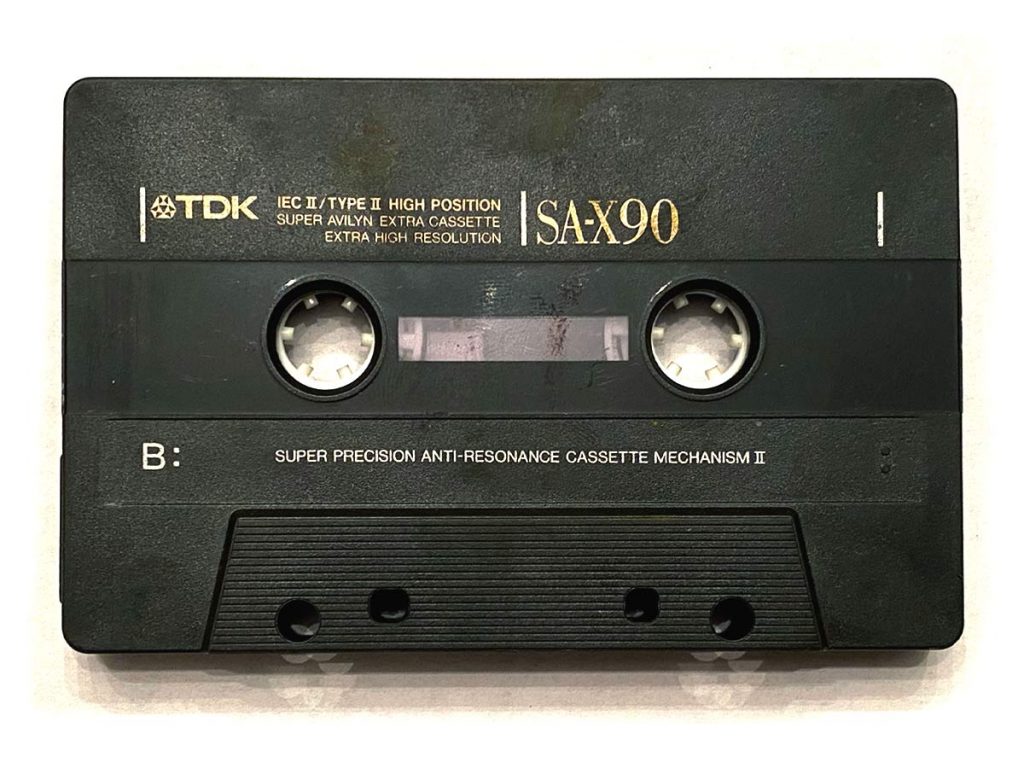

As I grew older, got jobs, bought music, how I made these tapes changed. I would still pull the occasional track from the radio, but I’d do it on my parents’ stereo system and a much better tape deck rather than my little boom box.

In the mid/late 80s, the compact disc (CD) was introduced and changed everything. I still had vinyl, official release tapes, radio, but the quality and speed of recording from a CD was a huge boon.

Another thing that changed around this time was the purpose of these tapes.

I still made tapes for myself, but increasingly I found myself making mixes for friends and, in some cases, to woo women.

At it’s essence, this is the transaction:

“I made you a tape.”

Subtext: Here, this is me. I trust you with me. Please be kind. I hope you like me.

“Oh! Cool!” Looks at tape cover. “Oooh, I love this song! I’ve never heard of half of this. I’ll listen to it later.”

Subtext: OK I’ll hear you out. I’ll let you know how I feel later, but I’m interested for now.

Any tape created for this purpose will have to do a few things:

- Convince them that you have listened to and care about them. (Insert a song you know they like early in the mix)

- And that you want them to know you too. (Insert a song you really like that you think they’ll like)

- But that you respect their space, choice, and their whole person as an amazing person (insert a song by their favorite artist/band)

- And if they’re open to it, the two of you could be something really special (insert a song you both agree upon, a potential candidate for “your song” as a couple)

- Also, I’m not a one trick pony. Here, get to know me better. (Insert songs that create the mood and message you’re trying to build with the mix)

All this is in the interest of building intimacy, a new relationship. Simple, right?

Not even close.

First, as an 80s teen, your supply of available music is limited by what you have on hand or is available at the local record store.

Second, 60 minutes is a lot of time to fill. It’s important to recognize that attention cannot be grabbed and held for even half that period. Not even in a pre-iPhone-everything-in-your-pocket-fill-every-second-with-something era. A single 60 minute block of awesome music would be exhausting. Pacing and sequence are critical to your success.

Last, context is super important.

Will they be listening to this on headphones? In a car? On a boombox in their bedroom? Their family’s stereo?

If it’s a family stereo, make sure you’re not dropping anything that’s going to sour you with their mom.

If you’ve ever tried to pre-program a mix to play in the background of a party on your computer or phone, you know how difficult it is to come up with something that’s going to engage and excite the room. Background music is easier, but this shouldn’t fade into the background—that’s not the message you’re trying to send. That means strategic use of volume and energy.

Got all that? Now go pick some songs.

There were essentially two ways of doing this in the real-time-recording era. You could do it live as though you were DJing to them on the fly or you can build a list and master a tape from the list.

Both methods require starting with a list of way too many songs to fit in the mix. Then edit. Pick starting and end point songs. Pick songs you can’t leave out. Establish some runs of songs that work well together. Think deeply about the above and whether you’re achieving your goal.

If you’re doing it live, start with the first song. While that song is playing, look through the remaining stack. What feels right for the next track? Pick it and go.

If you’re organizing the whole thing upfront, go ahead and make that happen. Expect to be surprised by what works and doesn’t and expect to go back and swap songs when they don’t feel right.

When you’re finished with recording, package it. Make sure you’ve included a track list with both the song title and artist. Be creative.

Remember, this is your soul you’re handing over, treat it with respect.

However, you should take it seriously only until it’s time for the handoff—this should be handled as breezily as you can muster. As much as you see this as a soul baring experience, it’s more likely than not that the recipient sees this is a simple mix tape, perhaps a chance to hear some good tunes you won’t hear on the radio.

And for god’s sake—don’t pester for feedback. It’ll come, or it won’t. But nothing kills a relationship faster than a constant need for validation.

This all probably seems like too much for a mixtape, but for real, this is how it went down for most of us. You’d spend 3-4 hours building an artifact as a soul proxy to someone else, pass it off casually, and hope for the best.

Admittedly, you probably didn’t spend quite as much time or worry over mixes for good buddies—they already knew how to plumb the depths of your soul whether they knew it or not.

In college, the mixtape became even more precious.

Who on earth had 3-4 hours to burn on a proper mix? I might come back from breaks with a tape to share, but time was at such a premium that it was a lean period for careful mixes.

I had a weekly show at the college radio station—I already had to come up with an hour-long mix every week so I often just recorded my show.

Somehow these feel less pointed, more wandering as mixes than others I’ve created over the years.

Unlike many radio stations, we had a freeform format which probably contributed to the meandering sets I was putting together. Live discovery is often a complete disaster and failure is an excellent teacher.

I recently tried to play one of these mixes for my family. They made me shut it off.

Seriously—they mocked me until I turned it off.

I briefly revived my mix making in the years immediately following graduation. At this point I was so all over the map with my music tastes that these tapes feel like an uncomfortable family reunion—there are people you’re genuinely happy to see and then there are others you’re not quite sure you’re related to. These were largely efforts at documenting a period of time rather than making cogent mixes.

I had come to recognize the value of my earlier efforts—that these tapes transcended nostalgia and reached a deeper part of me that connected me with myself. I didn’t want to lose track of this time in my life and rather than write a journal, this felt like a valid exercise—a way to shake loose reluctant memories.

Memories like the day my roommate and I had a 4 foot long lizard chase us around our apartment.

The lizard was supposed to be a pet. My roommate swore that when he was in the pet store it had sat all docile-like on his shoulder with his tail around his neck. I admit, there’s something cool about having a 4 foot lizard draped around your neck. It’s not my thing, but I get it. It’s not something you see every day and he apparently bonded with the beast right then and there.

So his girlfriend bought it for him. Even though he lived in a 2 bedroom apartment. With me.

And just like that we had a third roommate. Who slept in a steel dog cage. Who didn’t like to live in a cage. Who hated the cage so much that it would stick its head between the bars and twist to see if its prehistoric skull were strong enough to bend the bars.

And it was. Thankfully not enough to enable escape, but bars were definitely bent.

This was the reason we also had a mouse living in our apartment for a week. My roommate had been told that the monster liked its prey fresh and that little white mice were a perfect treat. Feeding a lizard that lives in a cage with openings wide enough for it to stick its head through, however, was a bit of a logistical nightmare. It was rare the the lizard would catch the mouse before it darted between the generously spaced bars. The result was a few free-range pets we imagined were nesting in my roommate’s closet.

If you’ve never seen an black throated monitor, you should check one out on youtube. They’re like a cross between a crocodile, an iguana, and a dinosaur. They’re fast, they have big claws, a long whipping tail, and are built like a tank. If you saw one in the wild, you would walk away slowly keeping your eye on it. The one in our apartment was big enough that you’d instinctively keep most dogs out of range.

I don’t remember how the beast escaped. I do remember climbing up on a chair (my roommate was up on top of the couch on the other side of the room) as a giant reptile prowled the hallway—pacing the length of the room and back to its cage—forked tongue slapping in and out, head bobbing back and forth. Hungry.

My roommate opened the windows—it was winter—remembering that the cold would slow down his pet and perhaps make it less whippy, scratchy, or bitey.

We eventually trapped it in my roommate’s room and closed the door. I have a picture somewhere of the thing tangled up in his window blinds, desperately looking for the warmth of its native sun—freedom—something better than the lot it currently had with us.

I think my roommate eventually caught it and brought it back to the pet store. I hope it eventually found a happier home with someone who could provide a more amenable environment.

Is this a story I’m likely to forget? No.

But the fact that the beast smelled exactly like maple syrup? That detail, along with a host of others, were brought forth thanks to a mix tape I’d produced the week before our prowler was set loose.

The tape wasn’t even playing while we scrambled around the apartment trying not to get bitten, scratched, or tail-whipped by an adult monitor.

But the monster made the entire apartment smell like maple syrup. It was probably the least expected attribute of the beast—its smell.

When I threw on that tape, not long ago, I smelled maple syrup—an olfactory flashback. Which reminded me of the monster. Which reminded me of that 3-ring morning we escaped certain doom at the jaws of a beast we kept in a cage on the floor of my roommate’s bedroom.

It’s never the purpose of these tapes to pull moments from the fog of memory, but that’s inevitably what happens.

The late 90s brought with them some transformative technologies for the music industry. Napster, iTunes, and other digital download sites lowered the average acquisition cost for music. You’d think this meant that we just spent less money, but you’d be wrong. It just meant that our money went further and our collections exploded.

These changes in distribution were happening at the same time as changes in playback technology. Where I had grown up toting a walkman cassette player around before upgrading to a discman, now I had an iPod and a couple thousand songs in my pocket. Mixes were asynchronous on the iPod—a song could be in as many mixes as I wanted but only had to be on the player once.

To feed that player you needed to have a digital collection so we all started ripping our discs to mp3s. And trading the files. Our overfed iTunes libraries got out of control and we could discover something new (and often terrible) within our own library just by putting all 50,000 tracks on random play. We stopped measuring our collection by the number albums and started measuring it in days.

When you combined this library with burnable disc media, suddenly it was super easy to make a CD mix.

It still took hours to put together the track list but the time accrued not from actually burning the disc but from selecting and refining the order of the songs in your mix.

When I was in high school I would acquire maybe 20 albums a year. Double that if you count the copies friends would make on tape.

In the digital age that’s about what gets added to my library every month—some in vinyl, but always digital.

Picking songs from that rabble of new artists, old flames, and the incredible variety of styles is what takes the most time.

In the early 2000s, I started making CDs for myself and my close friends. It started as an annual mix. I’d press 10-15 copies with fully designed jewel case inserts and disc labels I’d print out at home on a photo quality ink jet printer.

The only thing these discs have in common with mix tapes is that they’re both collections of songs.

Where the objective of a mixtape was to provide access to your soul, convey a message, or otherwise have a personal conversation with someone you care about, these mixes are best classified as time capsules.

Some include tracks recorded from vinyl, but those tracks are always digitized well in advance of mixing so even that part of the the process is completely different.

The result is something that’s bordering on professional production—kind of like an alternative NOW This is Music compilation for the indie crowd.

Since I’ve always been surprisingly retentive about keeping my iTunes library organized with playlists set to display albums that were added to my library in monthly increments, identifying the breadth of available options is easy.

First, I create a new playlist folder for the year under the “bests” folder and add a new playlist.

Then I pull up January. Display by album.

I’ve heard all these albums at least once. Some have been on repeat. Some have songs that have made it into a running mix, Others weren’t as great as promised and have been collecting dust.

There are clues to what’s going to fit from each album. Play count helps a bit. iTunes ratings help too. But nothing matters more than context.

See, I’ve already got at least 4-5 bangers primed for the mix. There are at least that many songs every year that I KNOW have to fit in somewhere. What I’m searching for is the glue.

Sometimes the songs I’ve picked are as disparate as Love Comes Close by Cold Cave and Mrs. Cold by Kings of Convenience. Getting from one to the other has to feel intentional otherwise the mix comes across like nothing more than a USB stick someone dropped with a bunch of mp3s on them—chaotic and incoherent.

I handled this in 2009 like this:

Love Comes Close by Cold Cave

This song is amazing on its own and acts as the crown jewel of the album its on. To date it’s the artist’s most popular song. It does, however, create a good deal of tension, something that needs a good release. Like…

I Knew by Lightning Dust

Banger in coveted #4 slot. Everything leads up to this song and its catharsis.

Sweet Disposition by the Temper Trap

One of the songs of the year—featured prominently in a well-loved summer movie. Steps back from the prior song yet an easy entry since most everyone has already heard it.

Monsoon by Delorean

Take a breather. A solid song that fits in with the vibe of the mix but doesn’t command your attention.

I Just Fell in Love Again by Quantic & His Combo Barabo

A left field, upbeat pseudo-motown song that’s super accessible, not indie, but something you probably haven’t heard before. Something that can work transitioning into…

Mrs. Cold by Kings of Convenience

A chilly, acoustic, proto-folk song that’s a rest spot for the disc. No surprises here—its a delicate and pretty song.

So in that list, what sticks out? Sweet Disposition was a gimme, that was going to be in there regardless. Every disc needs an easy entrance and this is that song in 2009.

I Just Fell in Love Again. What a song! Until I heard this mix again, I’d completely forgotten the song existed. I had to wait to get home to look up who performed it. But when I heard it, 2009 came back to me in a way that the super popular songs that have been staples of other mixes really don’t elicit. This song is fantastic. And I added it on a lark mostly to bridge indie synth-rock with Swedish folk.

When I was in high school the best mix tape I ever owned was the soundtrack to the movie Pretty in Pink.

If I go back and listen to that soundtrack, it’s not the obvious songs that bring me back to the 80s, it’s the deep cuts—the Suzanne Vega addition that was nearly overlooked, or Morrissey pleading to finally get what he wants—that transport me back to that time.

In 2011 I made what has likely become my final disc for public consumption. I made enough copies for co-workers and family and brought a bunch of them into the office. I handed them to my peers with the expected response—“Thanks, this is cool, I’ll probably never listen to it” but got an entirely new response from the office millennial crowd—“Uh, thanks? I think I know where I can find a CD player. You have mp3s?”

For the first time in my life I was the guy using outdated tech. It stung.

So how does one accomplish the goals of a playlist in the modern era?

In the age of streaming, the answer is a shared playlist on spotify, or your streaming service of choice I suppose. Maybe it’s filling a usb drive with numbered tracks. Maybe it’s making a CD and rationalizing that the only people who care about mix tapes anymore probably still have a CD player kicking around somewhere in their house. Lately I’ve been making single track mixes and then putting them on an online service that maintains the original crossfaded mix and recognizes songs to that artists are compensated when their work gets played. It’s still imperfect though—to hear it you have to use their proprietary player.

I’m not sure what the answer is because I haven’t cracked the code. I still share music with friends, but far less than I used to. I make annual mixes that end up being playlists in iTunes and single 50 minute epic mixes shared through Plex. Some of the people I know who actually looked forward to my mixes are marooned without a CD player.

I’m still making my mixes though. My audience has shrunk back down to something a little more focused—my wife and daughters.

Go right back up to the start of this chapter and read about the tape making process—I’m back in that zone although finding an entry point for an 8 or 12 year old is a bit harder these days. I think Taylor Swift may have made a cameo a year or so ago. Lorde is a staple in my home—a great crossover artist.

I’m still not cool, but maybe not as square as I could be.